A few days ago, I was inspired by a frustrated (I think we should give more credit to frustration as inspiration) article written by Tanya DePass of I Need Diverse Games. Her article led me to think about what I do in both my consumption and production of media with regard to people that are different from me and experiences that are different from my own.

Note – Before I dig into this topic, it’s important to acknowledge that anything I say here is built on the work of many other people who have done much more thinking about this than I have. If you are a writer of any kind, you should absolutely read Writing the Other by Nisi Shawl and Cynthia Ward. That’s a good place to start.

In Part 1, I focused on the idea that I benefit as an audience member because of the existence of heroic characters that are not like me. If you’re having trouble with the creative aspect, keep going back to that. Consume as much media as you can that features unfamiliar experiences and really try to take it in. Build your empathy a little bit before you start trying to write.

Writing to Be

So many of the problems writers run into when writing the other come directly from the act of “othering.” Flat, unrealistic, and stereotypical characters and scenes result when we focus on how they are different from ourselves and our own experiences – when we ask, “How would such a person in such a situation think or act?” and then believe we already know the answer.

So instead I ask, “How would I think or act if I were such a person in such a situation?”

This shift in questioning accomplishes several things. First, it makes the character’s lived experiences more real to me as the author. I am acknowledging the humanity and personhood of the character as not just valid (which is a weak form of acceptance) but equal to my own.

This then encourages me to reject any superficial understanding and pursue deeper research and consideration of the many issues involved. As soon as I think to myself, “I don’t actually know how I would think or act in this scenario,” I am immediately aware that there is more for me to learn. If I fail to put myself in the character, then I am much more likely to make inaccurate or even harmful assumptions.

And all of this is designed with the idea that the final outcome provides me with a character that I want to be (as described in Part 1). That’s the key – writing characters I want to be. That doesn’t mean they’re without flaws, but that I admire them enough to aspire to their strengths. That I would be happy to be compared to them.

We see all the time in movies, comics, and TV shows where men write women that they want to be with – the strong but sexy fighter, the manic pixie dream girl, the snarky but faithful wife, and so on. I say – Stop that. Write women you want to be.

Just think for a second how dramatically different our media would be if men consistently wrote about women with that simple guideline.

And that goes for every character you write, regardless of their ROAARS identities. Make characters you want to be, and that will go a long way to making characters your readers want to be as well.

Bass Reeves and the Lone Ranger Problem

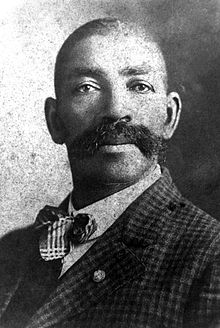

Anyone who is familiar with my work on Steamscapes will know that I am a huge fan of Bass Reeves. If you haven’t heard this name before, let me tell you that he was probably the most amazing lawman the Old West ever knew.

Even if you aren’t familiar with him, you may know some of his stories. Many of his exploits became the fictionalized tales of The Lone Ranger.

Many people have said that the Lone Ranger was based on John Hughes (among the people who said so was Hughes himself), who was actually a Ranger in Texas while Reeves was based in Oklahoma. But Hughes never disguised himself. He never had a Native American companion. And he didn’t leave silver dollars as a calling card. Reeves did. Yet because our culture couldn’t accept a black hero, they had to steal his stories and put a white face on them (which is basically the opposite of wanting to be someone).

Even if The Lone Ranger was based on a combination of the two or even a pastiche of rangers and marshals throughout the West, this example still illustrates the core problem that we have in our media – we are more willing to celebrate a fake white man than a real person of color. (Fake because it’s not like kids in the mid-20th century grew up playing “John Hughes.” They played “Lone Ranger.”)

But I would rather be Bass Reeves. And because I design roleplaying games, I have made sure that he already exists there, but I want more. I want a movie, a TV show, a comic book. I want everyone to want to be Bass Reeves.

And that’s just the start. There are so many more people we can want to be. Let’s write them!

If you would like to pursue this topic in more detail, especially as it pertains to game design, consider signing up for this class being given by Monica Valentinelli and K Tempest Bradford. Registration opens this weekend!